French troops landing in Bamako- Jerome Delay

2013 should have heralded a long respite from armed international interventions. On one hand a United States eager to avoid a second Libya and in the middle of distracting fiscal battle. On the other hand a cash-strapped Europe reducing its footprint, even in international aid. France itself snubbed the Central African Republic’s call for French help in staving off the advance of an armed group on its capital just two weeks ago. Armed military intervention should not have been anywhere near the top of the agenda.

This makes the French decision to intervene militarily in Mali last Friday, bombing key cities and lines to stop the advance of the Islamic militants all the more incomprehensible. The rest of the international community, though not absolutely enthusiastic, has pledged different amounts of military and intelligence support to the French’s Operation Serval, including troops from Nigeria and other African countries.

But why now, and why Mali? The following points are the main reasons that have been given by the media, politicians and experts over the last week to justify the sudden military intervention. Some, you’ll see, make (only slightly) more sense than others.

1. “We cannot allow the terrorists to gain a foothold!”

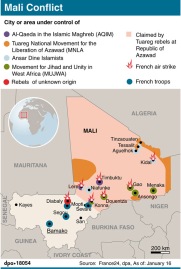

Map of the Malian conflict- The Atlantic

This is by far the most popular line of reasoning to come out on the news platforms and in the interviews.

The idea is that the principal threat posed by the armed extremist groups (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb or AQIM, Ansar Edine and MUJAO) comes by virtue of their animosity towards the United States and Europe. Allowing the terrorists to ‘gain a foothold’ in the country is an enormous security risk for western countries. Says U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta: “We have a responsibility to make sure that al-Qaida does not establish a base of operations.”

Two things are worrisome about this reasoning.

The first is that political discourse on intervention in the Mali affair constructs a dichotomy in African conflicts. On one hand there are the ‘conflicts as usual’, which are supposedly homegrown rebellions stemming from either ethnic, religious or resource allocation disputes. Senegal, Guinea, Central African Republic and Côte d’Ivoire are a few examples. On the other hand, we are told, there are ‘new’ conflicts more worthy of interest on the part of western states because they are linked to terrorism and are fundamentally transnational in origin. The Malian conflict is not about Mali; it is about the ‘transnational terrorist threat.’

Violent religious extremism is significant, but it is not the entire story behind the conflict. There is the Touareg independence agenda, power struggles among the different armed factions in the north, the March 2012 coup d’état to consider. There is the economic aspect: several leaders of Ansar Dine and MUJAO are also heavily involved in the illegal gun, drug and cigarette trade routes passing through the country (the man behind the recent hostage crisis in Algeria, Mohktar Bel-Mohktar, is also known as ‘Mr. Malboro’ for his involvement in Sahel cigarette smuggling). There are political aspects: negotiations with the Malian government aiming at forming the ever popular gouvernement d’union nationale– otherwise known as the divvying-up of ministry positions and national wealth. This is not an entirely terrorist conflict, and treating it as such is a dangerous idea.

The second reason to worry about the ‘standard’ and ‘new’ African conflict dichotomy is that, even admitting that the conflict is primarily one of combating terrorism, it is unclear to what extent military intervention will contribute to solving matters. Paul Pillar wrote a very interesting piece to this effect recently, essentially saying that combating terrorism in geographical terms is a misunderstanding of how terrorism works.

We […] apply [flawed] thinking to terrorism, which is a tactic and not an empire, partly because of a general tendency to think in spatial terms. Habitual and loose use of the label “al-Qaeda” also reifies a single global terrorist organization that does not really exist, as distinct from collections of groups that have adopted the al-Qaeda name or pieces of its ideology. – Paul Pillar

To this argument one can add the so-called spillover effect. The transnational nature of the terrorist threat in Africa, we are told, means that the Malian conflict can spill over to neighboring countries as well, fomenting unrest across borders in a 21st Century twist on domino theory.

To this, we can answer that the spillover has already happened, and that a while ago. There is also the recent Algerian hostage incident. What’s more, sudden intervention on the part of France means that there is no time to make sure that the armed groups’ strategic retreat will not precipitate a spillover of some sort in Niger, Algeria or Mauritania. In trying to stem the spread of conflict, this French action may end up aiding it.

2. “Mali is strategically located!”

The United States hiking up its military presence in Africa speaks to the growing (worrying) interest in the ‘strategically located’ African continent. This discourse is directly linked to the previous reasoning. ‘Terrorism cannot be allowed to wield influence on the continent’- and more precisely in the Horn of Africa and in West Africa.

The problem is ultimately that ‘strategically located’ is a judgment that comes from the country doing the intervening. What what is reflected in this word ‘strategic’ is nothing more than a country’s interests. As it happens the fight against terrorism has been labeled as in the interests of all countries. Soit. But the diagnosis of threat and the resulting action is still always at the discretion of the influential international players.

3. “Mali was an exemplary democracy that needs to be saved!”

Having gone through a couple of relatively problem-free elections and having built up a peaceful and functioning political system, Mali was for a time heralded as one of the stable and promising democracies of the region.

But the coup that ousted President Amadou Toumani Touré in March 2012 happened…..in March 2012- almost a year ago. Consolidating democratic rule in Mali since then has been very troublesome, not in the least because the northern territories are occupied by armed groups. Still, the type of rapid intervention we have seen in the past week may eventually restore government control over the physical territory, but it cannot guarantee the advancement of democracy. That role goes to the Malian people.

March 2012 Malian coup leader captain Sanogo- The Hindu

Incidentally the idea of saving Bamako from being taken by Islamic extremist groups, while a noble one, highlights the absolute arbitrary nature of interventions (in general but in this case) on the African continent. Just a couple of weeks ago the Central African Republic’s President François Bozizé launched a distress call to the international community, faced with a rapidly advancing front of armed rebellion. Sound familiar? (To be fair, the comparisons end about there, and experts I have talked to agree that there was practically no way that the unsavory Bozizé would have seen his capital collapse, protected as he was by an regional contingent of troops and his Chadian benefactors). The point remains that once you agree with interventions, you need to provide a logical answer to the question ‘in what case?’ This has yet to be done.

4. “We need to stop the spread of Sharia law and human rights abuses!”

In my mind this point should be the most heard and the biggest source of attention. From the wanton destruction of religious building and cultural patrimony to the indiscriminate meting out of punishment for smoking or listening to music the Islamic extremists in the north of Mali have, for the time they have occupied the territory, tried to institute Islamic Sharia law on the populations under their control. The logic for intervention in this discourse comes from a ‘right to protect’ reasoning, saying that the Malian state and armed forces are not in any shape to handle the threat to the people (side note: did you know that the Malian army of only 7,000 troops counts 59 generals?), and therefore military intervention is necessary for their protection.

So yes to the goal, but still no to the rapid, precipitated military response from the French. There were plans for

Islamic fundamentalists destroying a tomb in Timbuktu- National Post

intervention at the regional level, and while they adopted a rather slow calendar, it was going to be a concerted effort lead by neighboring countries. Rapid intervention, no matter how welcomed by the Malian government or people it is, creates the potential to increase insecurity in the country.

In short, Mali’s is not a different crisis, one that would justify the nature of the international intervention we have seen so far. In that it is a textbook case of many root problems of politics and conflict on the continent, Mali is not different.

Yes, interventions can be necessary. But I would like to see fewer interventions and more engagement. Mali is in a very complex situation, and heavy armed intervention can do more harm than good. Scrambling the fighter jets in time of crisis is a short-sighted solution to a problem that demands time, that demands advising, cooperation, consolidation of state capacities, security sector reform, reform in the aid regime and a host of other slow but sure(r) paths to peace. Engagement starts long before the guns are drawn, and I think that is the biggest failure of this whole affair.